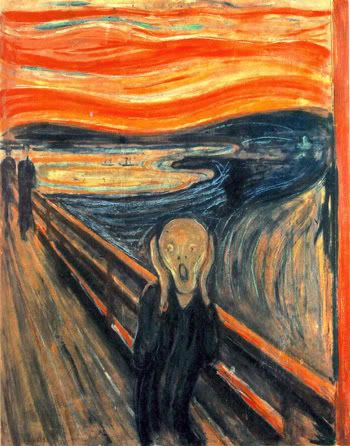

Who knows what directions are lives will take? Who knows what events will transform and shape our lives into versions of ourselves we never thought possible? And who knows what forces are out there that move us forward and drive us inexorably to the precipice of the most profound decisions that will either save us or damn us (or perhaps both) for all time?

Who knows what directions are lives will take? Who knows what events will transform and shape our lives into versions of ourselves we never thought possible? And who knows what forces are out there that move us forward and drive us inexorably to the precipice of the most profound decisions that will either save us or damn us (or perhaps both) for all time?

Such is the power of The Falls, in which the Niagara River, its rapids, its whirlpools, and its mighty Horseshoe, Bridal, and American Falls, is a constant underpinning current of the narrative, and perhaps, even a character in its own right.

"You realize that the speed, the proplulsion, has nothing to do with you. It is something happening to you."

Oates is dead on in her description of what happens when you're in the Niagara River and you pass the Deadline. You are caught up in something that is happening to you. I don't know if Joyce Carol Oates has ever gone whitewater rafting, but I raft Class IV and V rivers about thirty days a year. I'll never forget my first experience out of the raft right at the Deadline of Class V Insignificant. Insignificant is a misnomer. There is absolutely nothing insignificant about Insignificant.

The naming of Insignificant is legendary. Early explorers of the Gauley River simply arrived at this point below a long rapid of rushing water, house-size rocks, violently crashing five-foot waves, sudden ledge drops, holes and nasty pourovers and proclaimed: “there’s nothing significant above this point.” Even to this day, with all the advancements in whitewater equipment, and clothing, and protective gear; and with the increasingly capable and experienced guides and outfitters who run the Gauley so routinely that many of the most formidable rapids that were once considered unrunable have been downgraded from “dare-devil and life-threatening” to “experts only” to “advanced” to “intermediate” levels of difficulty; Insignificant remains categorized as a true “experts only” Class V rapid.

To put the significance of Insignificant in perspective for those of you who have never gone whitewater rafting or kayaking, a typical exchange between a guide and rafters after cleaning Insignificant might go something like this:

“Wow! That was awesome! What class was that?” Asks the adrenalinized rafter.

“That was a true Class V,” answers the bemused guide, who has been asked this question a thousand times in the last two weeks.

“That was a Class V? Wow! Is there anything bigger?”

“Oh yeah, there are lots of rapids that are bigger, longer, steeper, more dangerous.”

“Really? Have you rafted any of them?” Asks the wide-eyed rafter.

“A few,” the guide answers coyly.

“Have you ever fallen out?” Asks another rafter, a little shaken by Insignificant.

“Oh yeah, I’ve had my share of nasty swims.”

The rafters remain silent, presumably contemplating what a swim of Insignificant might have been like if one of them had fallen out of the raft.

“But Insignificant isn’t the most difficult rapid we’ll see today,” the guide says. “There’s still Pillow Rock, Lost Paddle, Iron Ring, and Sweet’s Falls.”

“Are they bigger than Insignificant?” Asks the timid rafter, now certain that he’s in way over his head.

“Not necessarily bigger,” answers the guide. “Lost Paddle is longer and more dangerous with more undercut rocks. Pillow Rock is bigger in every way, but safer. Iron Ring is short, fast, and steep; and Sweet’s Falls is the highest.”

“And…they’re all Class V?”

“Actually, only Lost Paddle is still a Class V. The other have been downgraded to Class IV+.”

“My God!” exclaims a fourth rafter. What would a Class VI be like?”

The guide takes a long pause and makes eye contact with each rafter in the raft. “Niagara Falls,” answers the guide with a sly grin.

The raft goes silent.

“Paddle forward!” Commands the guide.

I admit it. I wasn’t ready the first time I rafted the Gauley. I was overweight. I was relatively inexperienced, having rafted only two previous times on Class III and IV rivers. But at least I thought I knew what I was getting into. I read books on river hydraulics, I learned the names of all the rapids on the Gauley, I learned what the hazards on the river were and what to do if I found myself out of the raft and heading towards one of them.

The day of my first Gauley adventure dawned cold, overcast, and with the threat of rain. It was forty-two degrees outside and the water temperature was only forty-eight. Wet suits, thermal underwear, wool hats and socks were all required. I felt apprehensive, but believed I was ready. I even had a carabiner clipped to my life jacket to clip onto a throw-rope if I found myself in a life-threatening situation. It’s laughable to me now. In a life-threatening situation, a carabiner is pretty useless and downright life-threatening in its own right if you clip on to a throw rope. But I still carry that gold carabiner with me on every rafting trip. It’s my security blanket. It’s my good luck charm. It’s the repository for my confidence while I’m on the water. Hey, if you think it’s funny, check out some hockey player superstitions.

As it turned out, only two of the seven other rafters in my raft had ever rafted before. I was the experienced one. Kristina had rafted with Joey Anderson, our guide, the previous weekend on the Gauley. My friend Matt had rafted in Colorado once, although not a river this difficult. The other five yahoos had never rafted before, but they were determined to go whitewater rafting, and they were determined to raft the best there was. Lucky me.

We got in the raft and Joey had us practice our paddling strokes. If we were going to make it down the river without flipping or any other serious incident, we had to learn to paddle together as a team. Unfortunately, the tiny fifty-plus year-old woman in front of me didn’t know her left from her right, nor forward from backward. So when Joey called “all forward.” She paddled backward—or at least she attempted to paddle backward. Her paddle barely scratched the surface of the water, not helping propel or control the raft at all.

The woman in front of her got nervous and froze when a command was called, afraid of screwing up. So when Joey called a command, she hesitated so long her strokes were always out of sync with the rest of the raft. She would hit her paddle against the guy’s in front of her or the frail fifty year-old woman in front of me, further hampering the movement of the raft and making Joey’s job of guiding more difficult.

The man in the front on the left of the boat proclaimed himself to be an experienced expert rafter. He proved himself to be nothing but hot air in the first warm-up rapid when he extended his paddle and pushed off rocks that passed by or kept paddling when Joey called for a stop. You might think pushing off rocks makes sense, but in rafting, sometimes rocks are used as aids in maneuvering. Instead of helping the raft, this guy was constantly pushing us out of the line we needed to be on to negotiate the oncoming rapids or turns.

The woman behind this man, while full of bravado and excitement on the bus to the put-in, quickly became an irritating whiner after the first warm-up rapid; incessantly complaining: “It’s cold…I’m so cold. These waves are so big! We’re all going to die, aren’t we? I don’t want to die!”

I kid you not. A whitewater river isn’t like an interstate highway. You can’t exactly stop at the next exit and get off at the mall. I turned around and looked at Joey and Kristina. We didn’t say anything. We just locked eyes with each other. We knew we were fucked.

Setting up for Insignificant, Joey told us the line we would take through the rapid. Joey told us about the undercut rock on the right, that if we fell in, we needed to swim away from the rock. Joey told us how important it was for us all to paddle together. This was a major Class V, and we needed to listen and respond to his commands. Joey told us to brace in and make sure we stayed in the raft. It was going to be bumpy at the top of the rapid, and no matter what , do not fall out at the top of the rapid. Alright, here we go. Paddle forward!

I responded and leaned forward to dig my paddle into the water. Unfortunately, the woman in front of me extended her paddle backward and fouled her paddle in mine. It’s the process of digging into the water that actually keeps you in the raft while you paddle. My paddle never touched the water. All my weight and strength I intended to use to move the raft forward went into a great big air stroke. It doesn’t matter what your intentions are if you violate a law of physics. In this court, I was guilty and I was going in. At the top of Insignificant.

Time froze instantly as the intense cold of the water penetrated my wetsuit, paddling jacket, and thermal underwear. Surprisingly, there was no fear. There was no conscious thought. No thinking: “Oh shit! I’m going to die.” No thinking: “Swim away from the rock!” No thinking: “Hang on to your paddle,” or “swim to the raft!” All there was was a feeling of intense cold, a moment of shock, and then a flood of adrenaline and warmth as my body shifted into survival high gear. And then, just perception and reaction as the primitive portions of my brain that act on instinct alone took over.

I remember every indelible moment as if my eyes, ears, and skin suddenly became digital recorders. I remember the bubbles in the gray-green water. Rising to the surface, gasping for breath in the trough of a wave just before its crystal tentacles crashed over me and dragged me under again. The feel of a rock lightly brushing the soles of my shoes before the bottom fell out and I tumbled over into deep water and then popped up to the surface again—just in time to catch a breath and close my mouth before a towering five-foot wave crashed over me and ran up my nostrils, popping up again, spitting out water, taking another quick breath, another monster wave…. And then the voice shouting: “Swim to the raft! Swim to the raft!”

Consciousness returned like a fog burning off, but all my strength had been sucked out of me by the cold water and my body’s struggle to stay alive. I extended my paddle shaft towards the raft and immediately was surprised I was still holding on to it. Cruelly, the other rafters couldn’t figure out it would be helpful to grasp my paddle and pull me towards the raft. Instead, they extended their paddle blades once they realized I was there, but which are impossible to grab hold of. Finally I slipped towards the back of the raft and Kristina and Joey grabbed my life jacket. As we reached the calm pool below Insignificant and I was no more at the mercy of the ender waves, I let go of my paddle and Joey was able to pull me back into the raft.

I collapsed on the floor of the raft, panting hard, completely out of breath. Joey asked if I were alright. I couldn’t talk, so I nodded. My glasses were still on, and much to my disbelief, I didn’t even get a scratch. Joey told me I had just missed the undercut rock. I was informed by a guide in another boat that I had been swept over the nasty pourover—where my feet had brushed against the rock—and that the other guides thought I would be trapped in the nasty hole below the pourover. And I was informed that I did a good job of swimming towards the raft and that everyone was amazed that I hung onto my paddle. I don’t even remember trying to swim. Chalk one up for primal instincts.

After a few moments rest while pulled over against the river bank, Joey helped me back to my seat. I put my arm around his back and then resumed paddling. Over the next twenty minutes while I slowly recovered and we headed towards Pillow Rock I didn’t get worried or scared, but instead I realized that I now had a glimmer of understanding of what being an animal must be like—without conscious thought, just possessing instinct, perception, and reaction. A lion stalking its prey does not think about how good a zebra would taste for dinner. A lion perceives hunger, lies in wait, and reacts to a zebra passing by; not thinking about the hunt, but rather just acting on instinct and learned behavior to make the kill.

Deep down inside, I realized that with conscious thought or not, human beings are animals that evolved in the wild. We might sit in front of computer screens and televisions in our climate-controlled offices and homes, but we aren’t meant to. We are meant to be physically active and to run and to hunt and to interact with our environment—not to stalk cold cuts in a deli. I’m not saying that I would choose a wild existence. But swimming Insignificant—or rather, being swept helplessly down the rapid like a lifeless twig—was the most primal, powerful, and humbling experience of my life. And I have never felt more alive than in that eternity of battling for survival—which as the VCR proves conclusively, lasted a mere twenty-two seconds.

And I also realized, probably for the first time, how fragile my life was. A few feet left or right, an instant sooner or later, and I could have crashed into a rock, been forced under an undercut and drowned, been trapped and recirculated in a hole like a sock in a washing machine’s spin cycle or like a piece of paper being flushed down a toilet. Swimming a Class V rapid is merely a euphemism. No one swims a Class V rapid. You are swept to wherever the river wants to take you. Insignificant is most definitely a misnomer. Next to the power of Insignificant, I was about as strong, or important in the general scheme of things, as a speck of dust.

Now multiply that by a thousand and you have the Niagara River and The Falls. Joyce Carol Oates is masterful in capturing the allure of the river and its ironclad grip on the psyches of those who visit it or who live in close proximity to it, in retelling its most famous myths and legends, in revealing its many layers and secrets, and its greatest horrors in the best tradition of on the scene eye-witness reporting. And that is actually a theme or a device Oates has turned to repeatedly in her writing. In We Were The Mulvaneys one of the sons was a newspaper reporter. In The Falls, newspapers report the vigil of Ariah Littrell waiting for Gilbert Erskine's body to float to the surface and create the legend of the Widow Bride of the Falls. Later, as Ariah's oldest son Chandler tries to talk an old acquaintance from school out of a gruesome murder, the eyewitness account mirrors CNN and network on-the-scene footage. And finally, old newspapers are the key to unlocking the past by recounting the day-to-day history of Dirk Burnaby's crusade in taking on the Love Canal case--an event that just happened to him, but which swept him away to his death as inexorably as crossing the Deadline of the Niagara River.

The basic structure of The Falls is very much a reporting of profound events and sometimes impulsive decisions that shape the lives of the Burnaby family in ways none of them ever imagined nor believed was possible:

--On his honeymoon, Gilbert Erskine throws himself into the Niagara River within 24 hours of their marriage.

--Ariah Littrell begins a stoic vigil, during which she is transformed into the legendary Widow Bride of the Falls.

--The manager of the hotel the Erskines were staying at in Niagara Falls calls his friend, respected lawyer and playboy Dirk Burnaby to come to his aid to help deal with the situation of the widowed bride.

--Over seven days Burnaby becomes smitten with Ariah.

--Erskine's body is recovered and every tiny detail is revealed. Ariah returns to Troy, New York.

--Burnaby impulsively drives to Troy to woo her, impulsively stopping to franticly pick up wildflowers to present to Ariah.

--Ariah unexpectedly transforms from a frigid bride to a sex addict in Burnaby's arms.

--Against all odds and while almost being shunned by both their families, the newlywed Burnaby's begin a family all their own.

--Burnaby encounters Nina Olshaker, takes up her cause and transforms himself from a good ole boy prosperous attorney to a pro bono pariah launching the first major class action lawsuit in the nation's history--to the detriment of his family's financial health, his professional reputation and ultimately his life.

--On the night before his marriage, Royall Burnaby has sex with a lady in black in a cemetary and comes to the realization that he can not get married.

None of these major events are directions any of the characters would have ever forseen their lives would take. All of the decisions made by the characters completely altered their lives. But none of these events or decisions were really deliberate or rational. The events just happened and the characters were swept helplessly along for the ride, like a log, or a body, or a rafter in the powerful current of the Niagara River. Just like the families that were victims of Love Canal.

Of course, while newspaper reporting can be informative, it is rarely art. The power of Joyce Carol Oates is her magnificent prose and her ability to create and draw characters like no other. As events happen to all of the characters of The Falls and their lives transform, Oates gets into each character's head and draws out every nuance of their thoughts and feelings. Their hopes, their dreams, their fears, their grief, their triumphs, their failures, their secrets, and how all of these things weigh upon their minds, the decisions they must make, and the paths that their lives must take.

As readers, we are swept along for the ride with no clue where Oates is going. As in a Class V Rapid, we go to wherever Oates wants to take us. And at the end of every hundred pages or so there is a penetrating insight--if we are paying close enough attention.

If you have been reading my blog, you know that while on my way to Denali on January 19th, 2006, driving south from Fairbanks, I was in a rollover car accident. It was an event that just happened right out of the blue, and it started my head spinning. When you survive something like that without a scratch, you think a lot about God and "what ifs." If you are injured in something like that or worse, if you injure someone else, it can really work you over emotionally and lead to self-destructive habits. I believe the lesson, or real insight, of The Falls is that when events happen that dramatically change our lives, there are times when we are caught up in the event and that we literally risk the danger of being swept away. Our saving grace comes when we realize that we are not prisoners of events that just happen to us, like a rollover car accident or falling out of a raft in a very bad place. After swimming Insignificant, instead of being fearful and afraid of whitewater rivers and adventure, I embraced rafting, and through rafting, life itself. In The Falls, Ariah's and Dirk's children are being swept away by the secrets of their past. It's only after Royall starts investigating the events surrounding his father's death and confronting the past Ariah has shielded them from since childhood that the Burnaby family can escape from a series of events that has swept them along like a log in the river since a distant Burnaby ancestor plunged to his death while walking a tight rope over Niagara Falls. It's only then that the process of redemption can begin, and the Burnaby family can fulfill the promise of their lives. It really is a lesson for us all.

Thanks for reading.

Technorati Tags:the falls, niagara falls, joyce carol oates, books, book reviews, literature, whitewater rafting, gauley river

Generated By Technorati Tag Generator